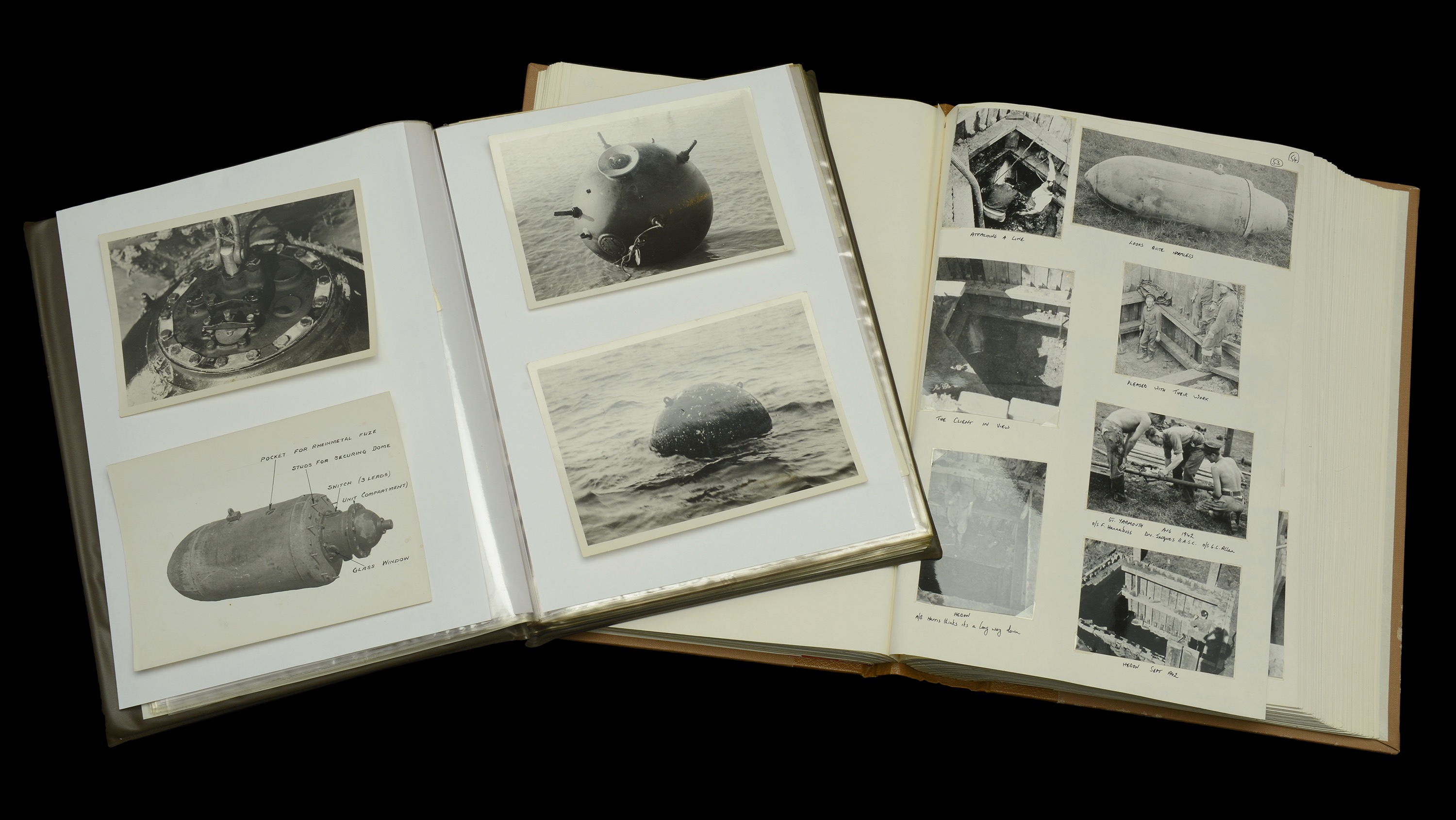

‘I have been much impressed with the report you sent me indicating the fine work performed by the Land Incident Section since its inception. The work of these officers and ratings, and the cold-blooded heroism with which they performed it, have been of the highest quality, and have been the cause of saving many lives and homes.’ Winston Churchill in a message to the First Sea Lord of the Admiralty, 10 January 1945. The important Second War bomb and mine disposal O.B.E., George Medal and Bar group of seven awarded to Lieutenant-Commander G. J. ‘Jack’ Cliff, Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve, who on one occasion was recommended for the award of a G.C. and had previously been decorated with the M.B.E. for like services, a very rare instance of ‘quadruple gallantry awards’ in the Second War Often working alongside his fellow Australian Lieutenant-Commander L. V. Goldsworthy, G.C., D.S.C., G.M., he became known as ‘Contractor Joe’ for his extraordinary skills in rendering safe deeply embedded ‘G’ type mines, thereby gallantly embracing the Land Incident Section’s informal motto to ‘get rid of the damn things’; described by one contemporary as being ‘slightly eccentric’ and ‘a bright and jovial man with a hearty laugh’, he also possessed ‘a remarkable capacity for drinking beer.’ And few, it may be said, deserved a crate of the amber liquid more than he, for his survival was nothing short of miraculous: On one occasion in the Blitz he was buried under rubble while working on a brute of a parachute mine in Bermondsey; on another, in tackling a badly damaged ‘G’ type on the Isle of Sheppey, ‘he worked on through a series of electric shocks and sparks due to the damaged switch, not knowing whether these were going to detonate the mine … ‘ The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, O.B.E. (Military) Officer’s 2nd type breast badge, silver-gilt; George Medal, G.VI.R., 1st issue (Lieut. Geoffrey J. Cliff. R.A.N.V.R.) with Second Award Bar, the reverse officially dated ‘1942’; 1939-45 Star; Pacific Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Australia Service Medal, these last three officially impressed (G. J. Cliff. R.A.N.V.R.) mounted as worn, very fine (7) £8,000-£10,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Spink/Noble Auction, March 1999. Just four Australians have been awarded the George Medal and Bar, a civilian and three officers of the Royal Australian Navy. O.B.E. (Military) London Gazette 18 April 1944: ‘For gallantry and devotion to duty:- Lieut. G. J. Cliff, M.B.E., R.A.N.V.R.’ - a promotion from M.B.E. (Military) awarded in London Gazette 28 September 1943. The 4-page recommendation describes the rendering safe of a mine which had fallen in Coal Barge Wharf at Southampton. The complex operation to recover the mine extended from August to October 1943, the concluding paragraphs of the recommendation stating: ‘At high water the (air) bag with the mine attached was towed from the dock through Southampton Water to Hamble Spit where it was intended at low water to make an effort to gag and remove the fuse. On the way to this spot, due to a leak in the bag, the mine sank to the bottom. Lieutenant-Commander Cliff was faced with the position of casting it off or dragging it as best he could towards the shore where it was hoped to beach it. This was accomplished not without alarm, and the bag and gear attended to, and the tow proceeded with. Upon examination at the next low water the mine was found to be a ‘GC’ type. It was seen that the fuse could not possibly be gagged owing to corrosion of its face. The keep ring appeared to be in good condition but could not be persuaded to move. Lieutenant-Commander Cliff therefore drilled the keep ring away from the case and again attempted to remove the fuse. This would not stir and owing to the absence of the screwed portion on the bomb fuse face, due to corrosion, it was not possible to utilise the extractor. Permission was then sought and granted for the removal of the mine to a safe spot at the entrance to the Hamble River where it was intended to detonate the filling. The mine was finally detonated on 7 October 1943, at high water, and very little damage to surrounding property was caused. The work carried out by Lieutenant-Commander Cliff and Lieutenant Goldsworthy was of the highest order. It had been found by experience that mines which have had charges exploded near them without detonation are extremely dangerous, and both officers were well aware of this. They are both recommended for an award.’ G.M. London Gazette 9 June 1942: ‘For gallantry and undaunted devotion to duty.’ The original recommendation states: ‘On 11 May 1941 an unexploded parachute mine was reported as having dropped on a two-storey building in the Leather Market at Bermondsey. The mine was eventually found completely covered by debris, and Lieutenant Cliff had to make his way through and below this debris to reach it. When he was about to commence operations another mine or bomb detonated nearby, completely burying him in wreckage and rubble. Lieutenant Cliff realised full well that this detonation was more than liable to have started the clockwork fuse in the mine with which he was dealing. With the greatest difficulty he managed to escape from under the debris by which he was buried, and immediately continued his operations on the mine which he successfully rendered safe. A further instance of the difficulties and onerous conditions under which he was working is provided by the fact that it was necessary to demolish the walls of the building before the mine could be removed. On 2 July 1941, a ‘G’ type Mine dropped at Leysdown, Isle of Sheppey. ‘G’ Type Mines are dropped without parachutes, and, if they do not explode on impact, nearly always bury themselves deep in the ground. Moreover, they contain not only a magnetic unit, which is presumed to be alive, but also an anti-handling device operated by a photo-electric cell. It is therefore necessary to work at the bottom of a deep hole and in darkness. In this instance the mine was badly damaged by its fall, making it even more dangerous, and was buried 24 feet down in clay soil. Lieutenant Cliff found that the clay had found its way under the cover of the mine and had shorn off the top plate of the switch. In consequence he worked on through a series of electric shocks and sparks due to the damaged switch, not knowing whether these were going to detonate the mine. He eventually removed the damaged switch by sheering off the six screws which held it. He then had to remove the bolts holding the magnetically alive unit with a hacksaw owing to their damaged condition. However, after nearly a month of hard and hazardous work he succeeded in rendering the mine safe. Between August to October, Lieutenant Cliff also successfully dealt with three other mines in the Thames Estuary District, which were endangering oil tanks at Thames Haven. These mines were covered with water and mud and were buried about 8 to 16 feet down. In each instance coffer dams had to be erected and the water pumped out, and each took between a fortnight and a month to recover. These mines were particularly dangerous, as previous attempts had been made to countermine them. Lieutenant Cliff was assisted throughout by Lieutenant Charles Graham Tanner, R.N.V.R. as ‘Learner’, and the excavating and timbering was done by Lieutenant Lombard ...